If you need any help, please feel free to contact us

How to Maintain Quartz Crucibles with Borax?

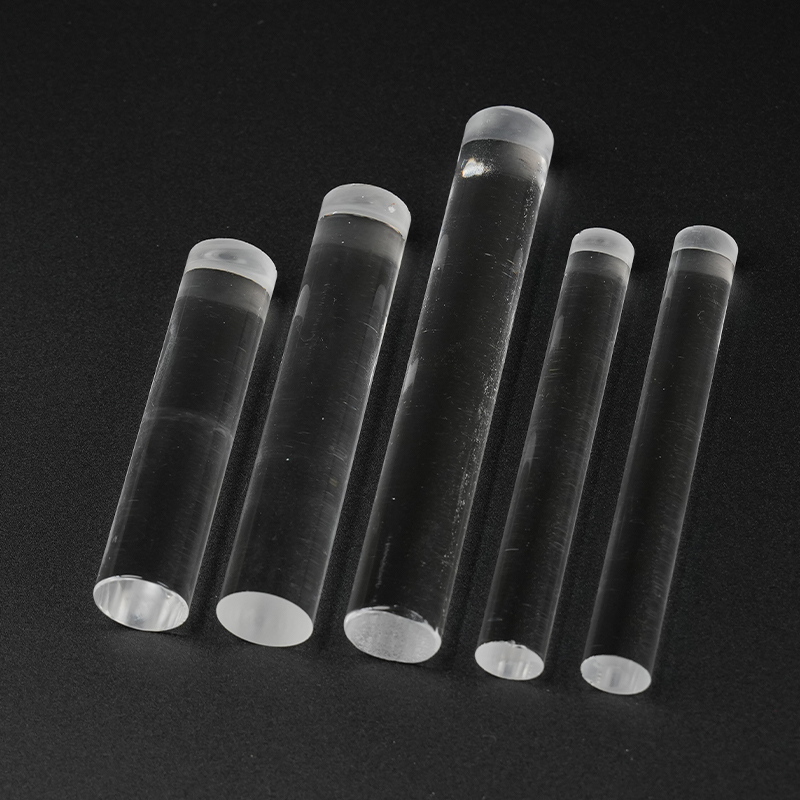

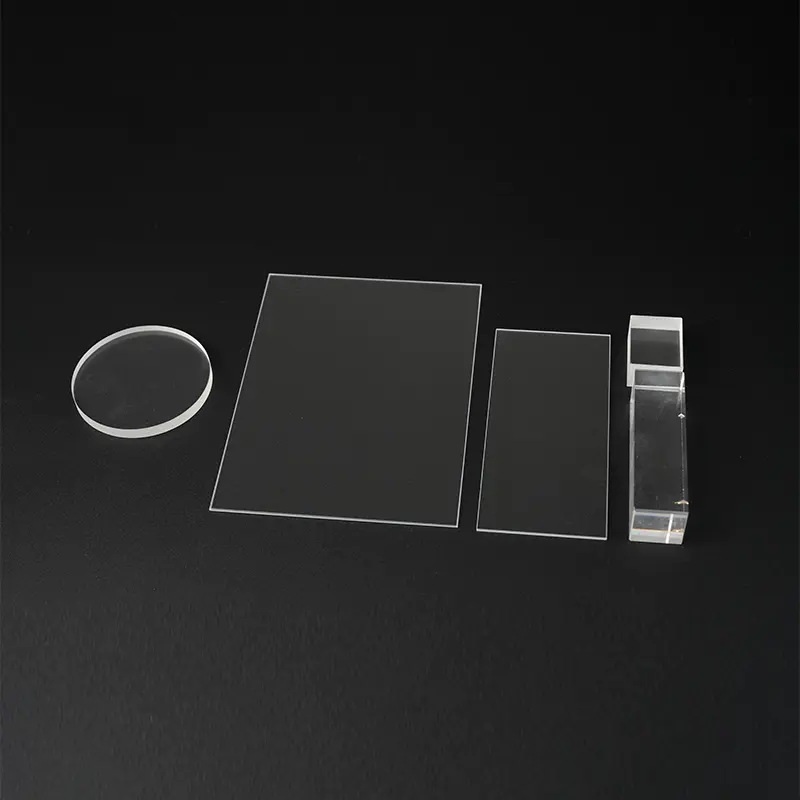

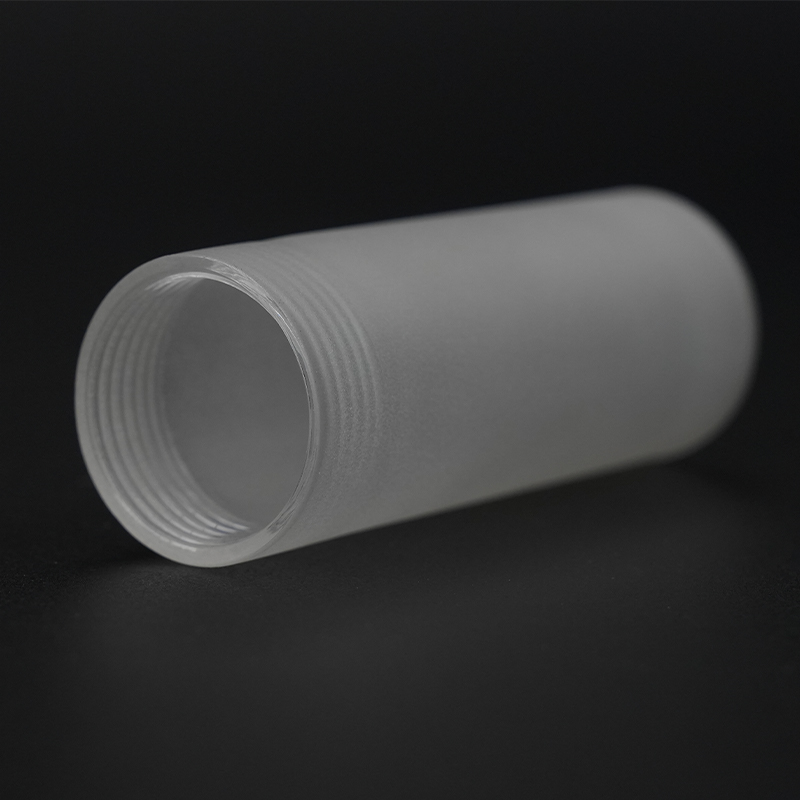

In high-temperature experiments and materials processing, quartz crucibles are indispensable key vessels. Their excellent high-temperature resistance and chemical stability make them widely used in industries such as semiconductors, solar energy, and metallurgy. However, quartz crucibles are susceptible to corrosion during use, especially when melting certain metals or oxides, leading to a shortened lifespan. Today, we'll discuss an efficient and common maintenance method: how to extend the lifespan of quartz crucibles using borax (sodium tetraborate).

Content

Why Do Quartz Crucibles Need Maintenance?

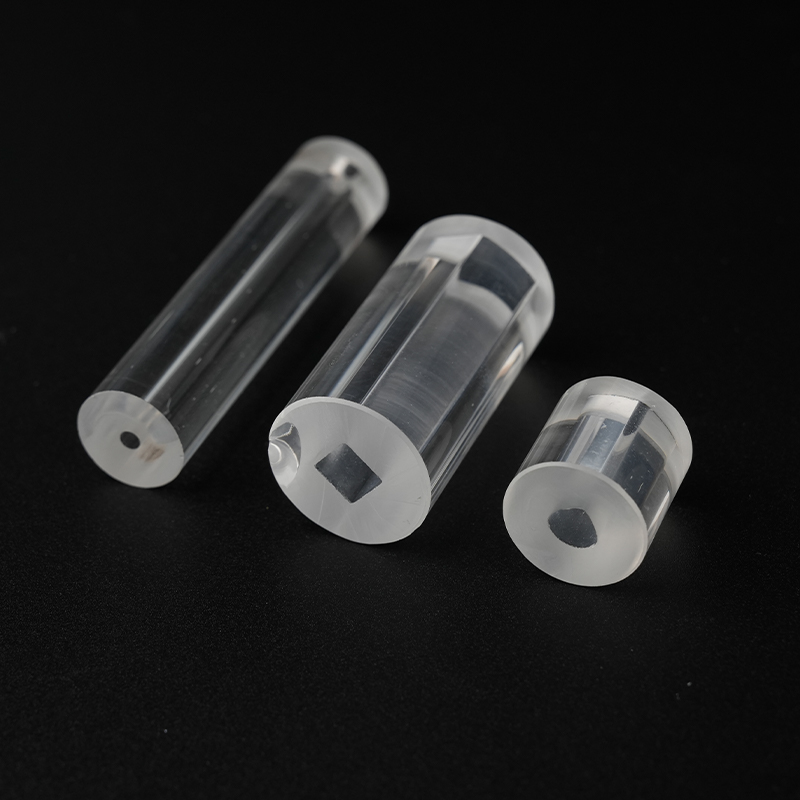

The main component of quartz crucibles is silicon dioxide. Although it has high purity, at extremely high temperatures, the inner wall of the quartz crucible may chemically react with the molten material, forming low-melting-point eutectics, leading to erosion, thinning, and even cracking of the inner wall. Furthermore, thermal stress at high temperatures can also cause micro-cracks in the crucible. Effective maintenance, especially the “glazing” treatment of the inner wall, is crucial for protecting expensive quartz crucibles.

Mechanism of Borax in Quartz Crucible Maintenance

Borax possesses unique properties at high temperatures, making it an ideal protective agent for quartz crucibles:

Forming a Protective Layer (Enameling)

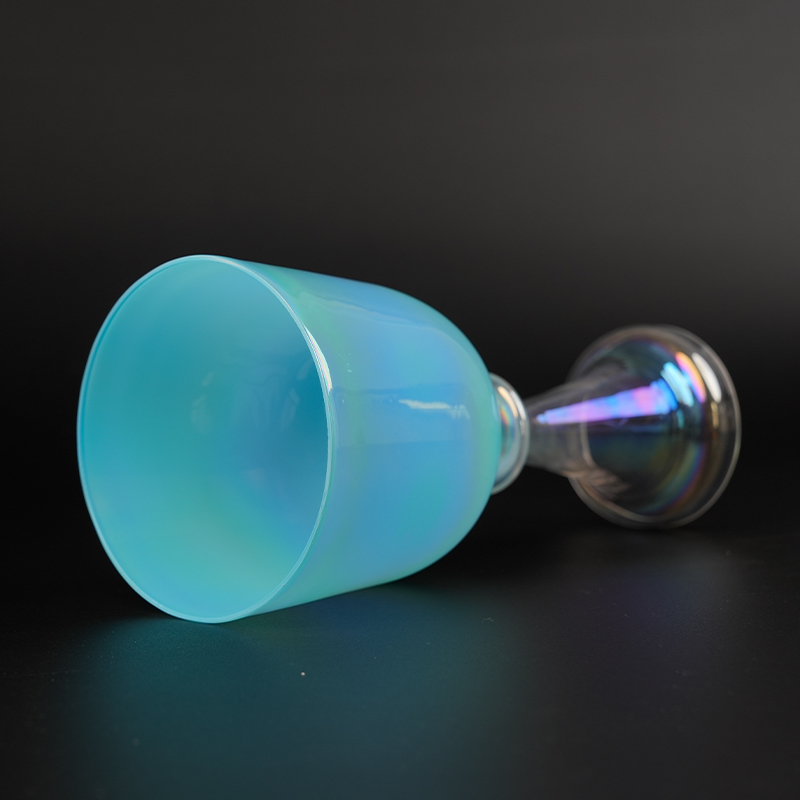

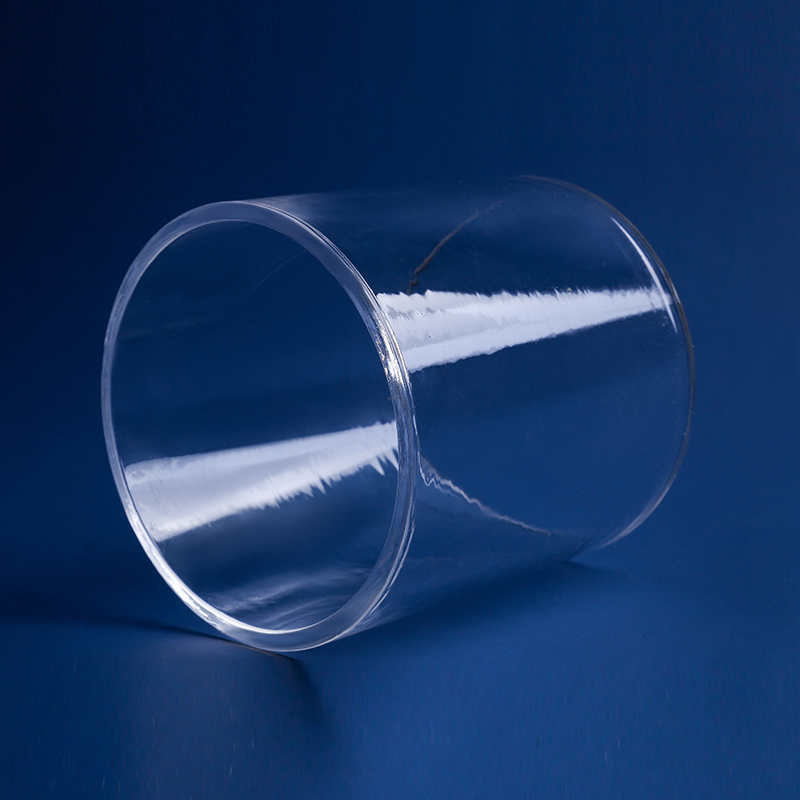

When borax melts at high temperatures, it forms a glassy melt, primarily composed of sodium borate glass. This glassy melt effectively wets the inner wall of the quartz crucible.

Isolating the Reaction

The formed sodium borate glass enamel layer adheres tightly to the inner surface of the crucible, acting as a physical barrier between the quartz material and the material to be melted. This significantly slows down the direct chemical erosion of the silica matrix by the melt.

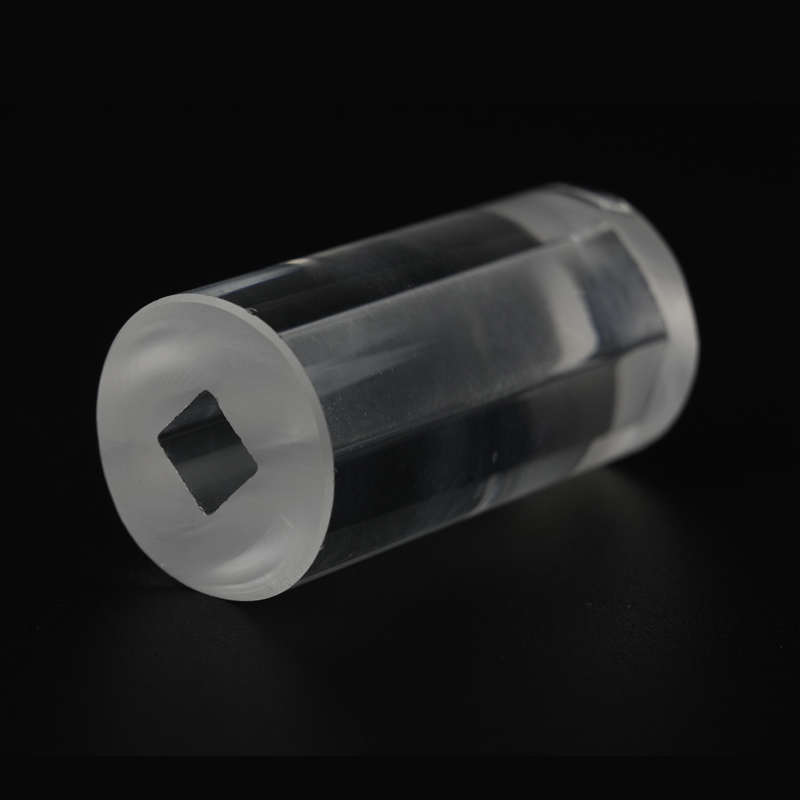

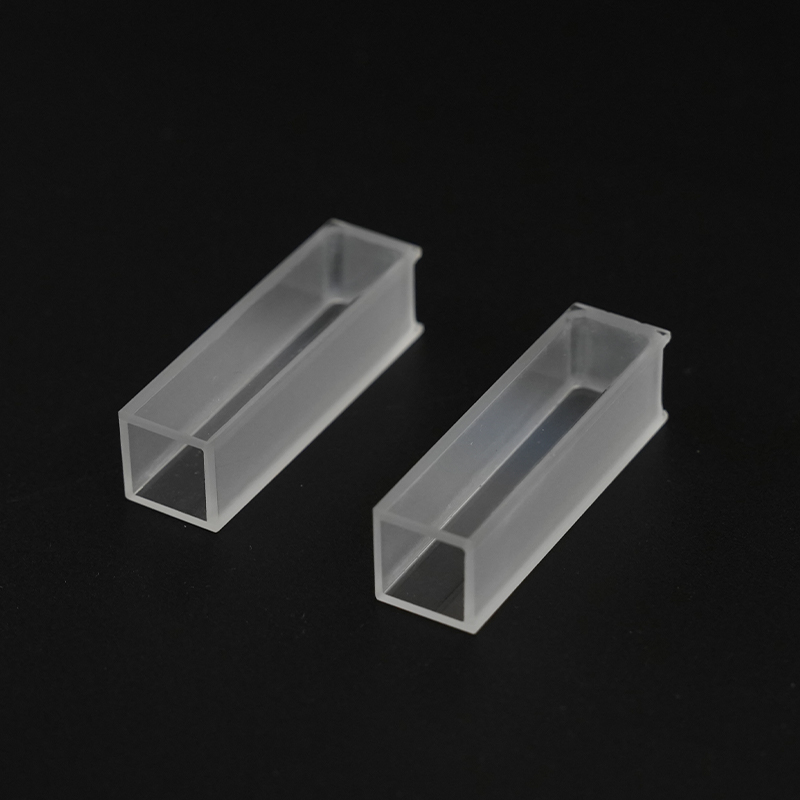

Repairing Micropores

The borax melt can flow into and fill the tiny cracks and pores on the surface of the quartz crucible, thereby improving the crucible's density and impermeability.

Detailed Steps for Borax Enameling Maintenance of Quartz Crucibles

The steps for borax enamel treatment of new or thoroughly cleaned quartz crucibles are as follows:

1. Preparation

Clean the Crucible: Ensure the inside of the quartz crucible is clean and free of residue. Old residues can be removed using dilute acid or high-temperature sintering.

Preparing Borax: Use high-purity anhydrous borax or decahydrate borax. Anhydrous borax is preferred because it does not generate a large amount of steam when heated.

Safety Precautions: Wear necessary protective equipment such as high-temperature resistant gloves and goggles.

2. Applying and Heating Borax

Uniform Coating: Sprinkle a thin layer of borax powder evenly onto the bottom and inner wall of the quartz crucible. The amount should not be excessive; a thin layer covering the bottom is usually sufficient.

Heating and Melting: Place the crucible containing borax into a high-temperature furnace and heat it to above the melting point of borax at an appropriate heating rate.

Rotation Wetting: After reaching the melting temperature, carefully and slowly rotate the quartz crucible using long-handled tongs to ensure that the molten borax flows evenly and fully wets the entire inner wall and edges of the crucible. This step is crucial for ensuring the formation of a complete glaze layer.

3. Cooling and Inspection

Slow Cooling: Stop heating and allow the crucible to cool naturally and slowly to room temperature in the furnace or a dry, insulated environment. Rapid cooling can introduce thermal stress, potentially damaging the quartz crucible.

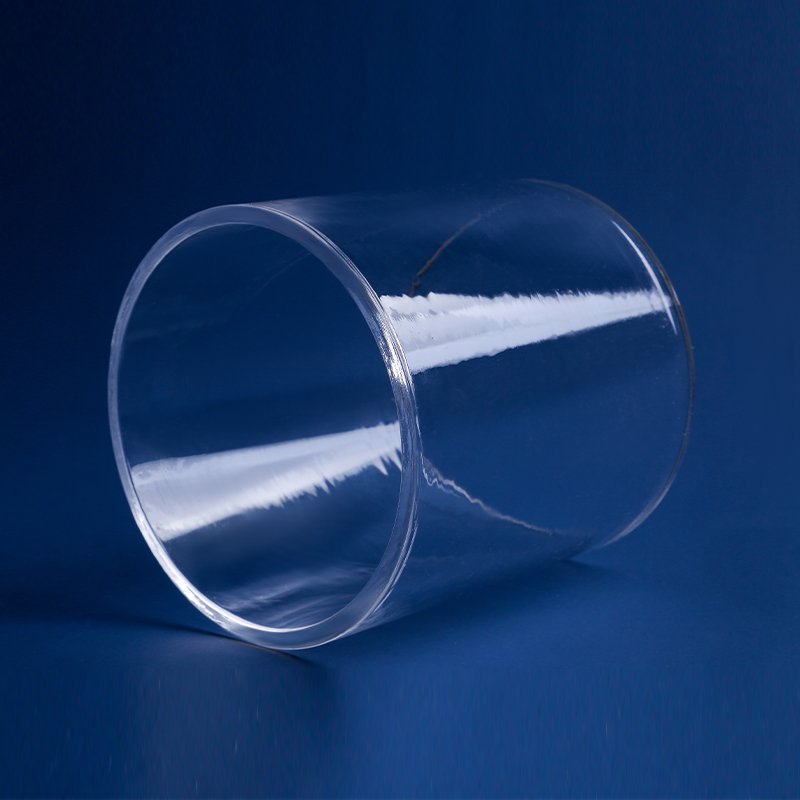

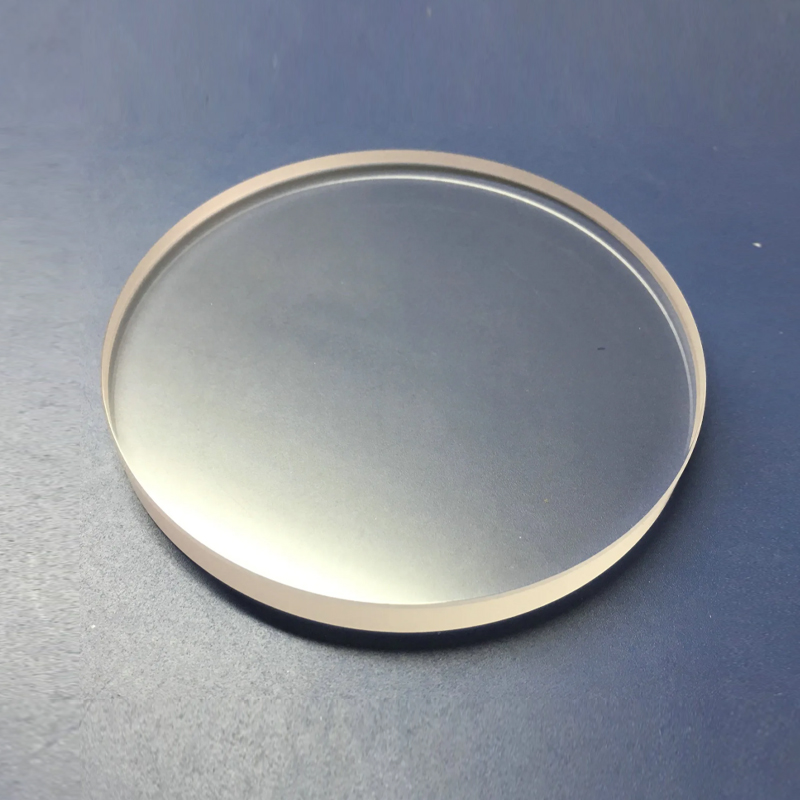

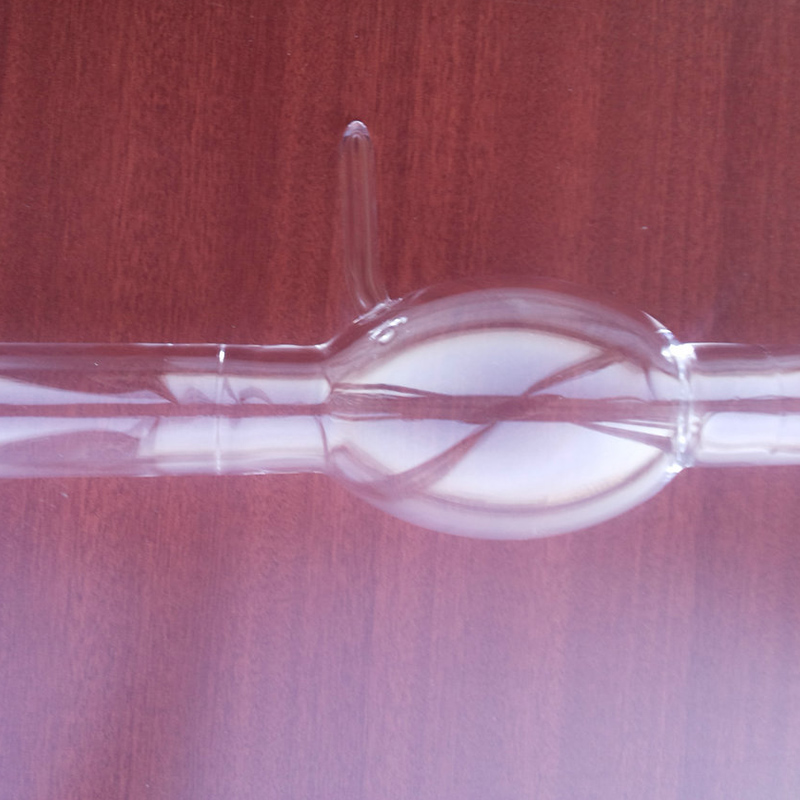

Inspect the Glaze: After cooling, the inner wall of the crucible should exhibit a smooth, uniform, transparent or translucent glassy glaze. This protective glaze is a sign of successful borax maintenance.

Boraxing quartz crucibles is a simple and efficient maintenance method. By forming a sodium borate protective glaze on the inner wall of the crucible, its resistance to chemical corrosion can be significantly improved, especially when handling alkaline or certain metal oxide melts.

Although borax effectively protects quartz crucibles, it introduces a small amount of sodium, which may affect certain experiments requiring extremely high purity (such as semiconductor single crystal growth). In such cases, the use of this method needs to be weighed based on the specific requirements of the experiment.

+86-0515-86223369

+86-0515-86223369  en

en English

English 日本語

日本語 Español

Español